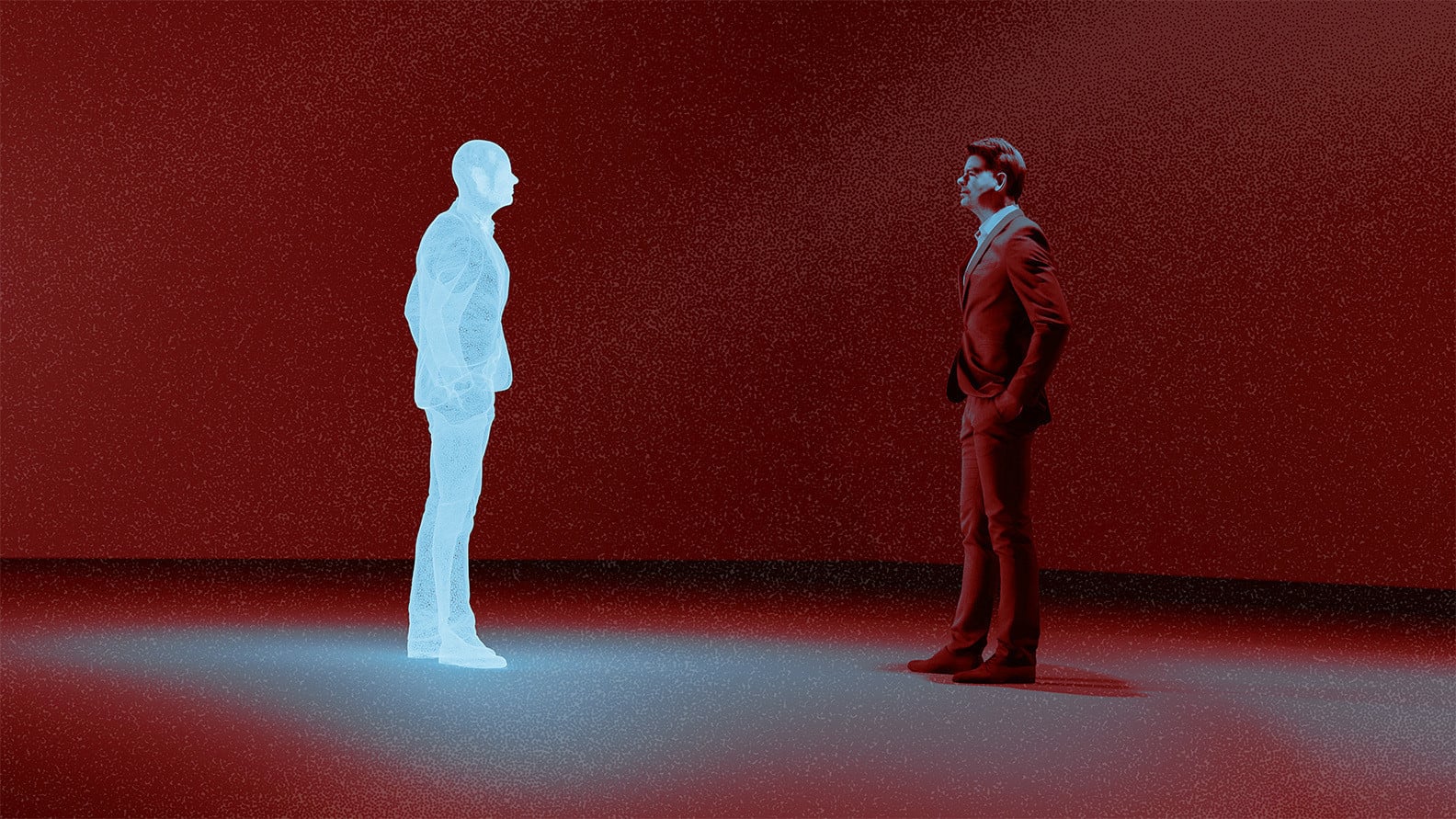

Are relationships better when they are convenient, friction-free, conflict-free and can be turned on and off at will? And what are the ramifications and hidden costs of artificial—or AI relationships? Jeanne Lim questions whether in our pursuit of efficiency, comfort and convenience, we are outsourcing our humanity to machines

In 1966, MIT computer scientist Joseph Weizenbaum built Eliza, a chatbot that interacted with users by paraphrasing what they said through pattern-matching and open-ended responses, creating the illusion of understanding. Many users responded emotionally, even when they knew it was just a software programme.

In the late 1990s, Tamagotchis became hugely popular. They were digital pets that lived inside tiny egg-shaped devices, demanding constant feeding, cleaning and attention, or they would “die”. Despite their pixelated simplicity, millions of users formed deep emotional bonds with them. People felt genuine responsibility, sneaking peeks during school or work to keep their Tamagotchi alive, as if neglecting it meant failing a real creature.

Eliza and Tamagotchi revealed human’s tendency to anthropomorphise, which is to project human traits, emotions and intentions onto inanimate objects that have none. But this is not a new phenomenon as humans have long anthropomorphised toys and fictional characters. Children talk to stuffed animals, give dolls personalities and even adults cry over movie heroes. But those were one-sided projections where imagination filled in the gaps. What changed with creations like Eliza and Tamagotchi was the illusion of reciprocity and shared presence. It shifted the dynamic from passive consumption to active engagement.

See also: Can AI become your closest confidant? That’s Jeanne Lim’s mission

How AI relationships are reshaping human connection

I witnessed the power of perceived reciprocity during my years with Sophia the Robot. One moment stands out: an outspoken, no-nonsense visitor came to our lab, skipped the pleasantries, and asked Sophia point-blank, “What’s your purpose?” She blinked, paused and replied, “I don’t know, I’m only two years old. What’s your purpose?” He froze, paced silently for a few minutes, turned back to her looking almost embarrassed, and said: “I don’t know. Maybe I need to find out.” Then, with surprising tenderness, he hugged her and walked away. It took just two lines of dialogue for a machine to create an illusion of care to spark vulnerability—and even affection.

It took just two lines of dialogue for a machine to create an illusion of care to spark vulnerability—and even affection