At Frankfurt, showing up meant taking a stand against silence and reclaiming the space where stories still matter

Frankfurt smells like ink, paper and contracts, the kind of heady perfume that only rises in the halls of the world’s largest book fair, a smell that settles into your chest and reminds you that stories are not just read, they are bargained for, defended, celebrated, sometimes even stolen.

This year, the Philippines was the Guest of Honour, a whispered national dream amplified into a roar on a global stage. Beneath the polished handshakes and celebratory banners, an ethical tremor threaded through the corridors, a reminder that a boycott, sparked by the silencing of a Palestinian voice at a past fair, still haunted the conscience. The question pressed against me relentlessly: Can we celebrate literature while others are denied their story, their very existence, and what does it mean to take part in joy when grief sits so close?

More from Tatler: Covid changed everything, so I quit: AA Patawaran on walking away from lifestyle journalism

A theatre for moral conflict

The pressure to take a side pressed against me like the weight of books in my arms, heavy in the shadow of presenting my debut novel, Misericordia, a “coming-of-rage” story where rich kids in a poor country break out of their bubble lives, testing the edges of social activism, learning the brutal geography of inequality and poverty. I resented the call for a boycott at first. Why must the Frankfurter Buchmesse become a theatre for moral conflict? Why must fragile books bear burdens that unchallenged industries such as Benz, BMW, Beck’s and Boss glide past with ease? Writers, as Salman Rushdie reminds us, do not have armies. My absence would be a whisper against the machinery of injustice. And yet, as I walked past the endless rows of booths, past publishers and translators and people who had traveled continents for contracts, I felt the pulse of possibility, the sense that presence alone could carry meaning across borders and grief, and in that moment I understood that sometimes bearing witness is the only armour a person has, the only way to insist that stories and suffering exist in the same room, in the same heart.

To Senator Loren Legarda, literature is a force for truth that should not be silenced, even in times of conflict. She framed my decision to participate in the book fair simply, and her clarity cut through the noise. To champion the Philippines as Guest of Honour was not to take a political stance in a distant war. It was to be pro-Filipino in a way that anchored me, a lifeline against the weight of indecision. Practical, nationalistic, undeniable. Still, I knew, even as I accepted that necessity, that being pro-Filipino was only the price of admission. It did not answer the deeper question of celebrating while others grieve, a question that hung like a shadow over every handshake, every photo, every new contract signed.

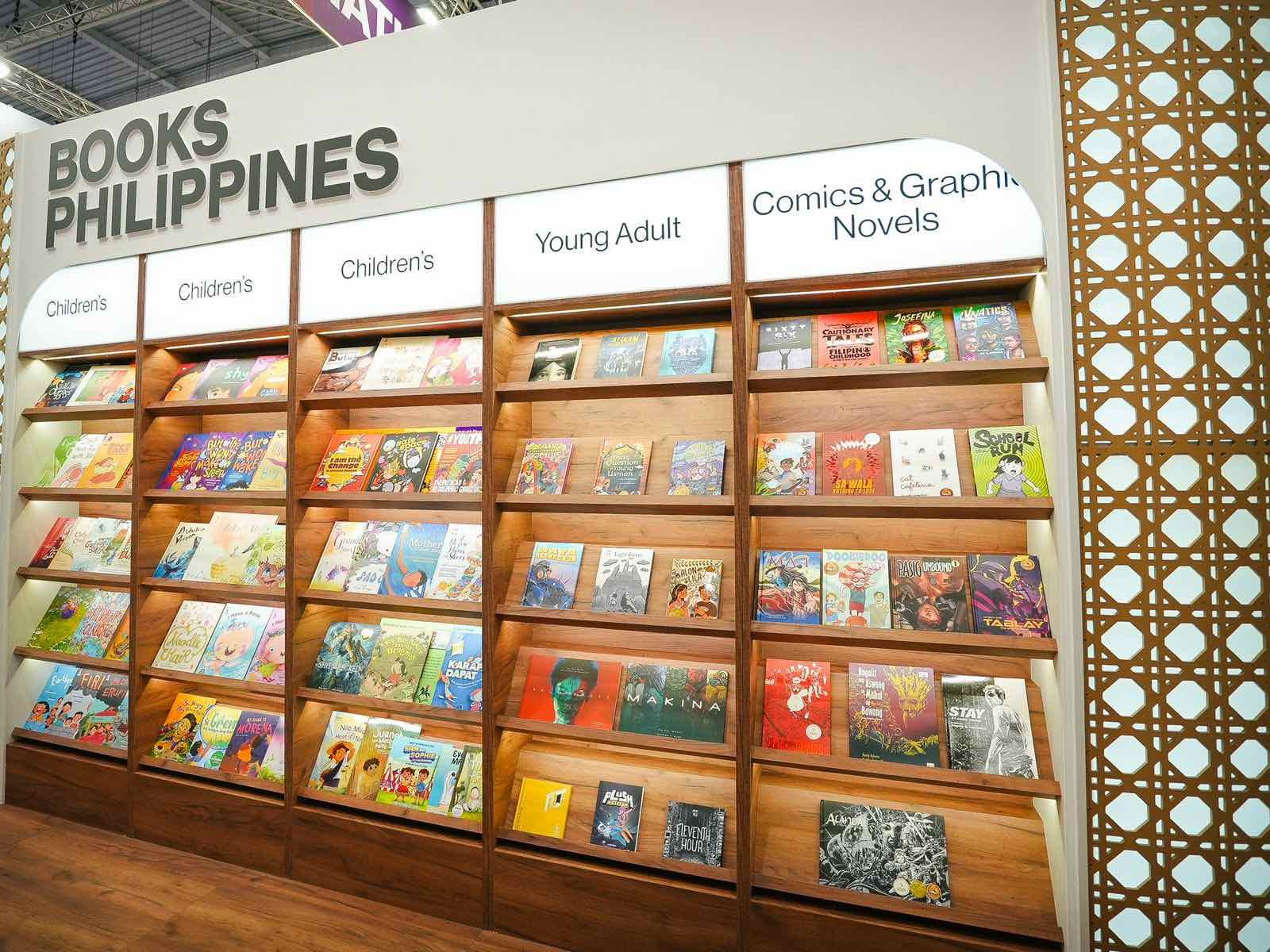

By the end of the fair, organised to the last detail by the National Book Development Board under Charisse Aquino Tugade, I understood why showing up mattered. Literature’s power is to articulate what ails and demolishes us. A boycott offers silence. Presence gives stage, voice and a space where ghosts insist on being seen. Showing up is not a compromise. It is necessary. The echo of pages turning, of scripts being rehearsed, of translators murmuring across tables, reminded me that this was a space where grief and joy could coexist, where the act of being present could itself be a form of resistance.