With “The Big One” predicted to strike Metro Manila in our lifetime, Mahar Lagmay, Filipino geologist and Project Noah executive director, dismantles a dangerous myth: that surviving an earthquake is just about ducking for cover

On January 1, 2024, my Japanese friend, Eizo Yamaguchi, invited us to celebrate New Year’s Day at his house in the suburbs of Nagoya, Japan. He prepared a nabemono hotpot dish with freshly picked vegetables, enoki mushrooms and thinly sliced Kobe Beef. It was a simple communal dish, but my family adored it. I could tell because they kept saying “Oishii” throughout the meal. After giving us Meiji chocolates for dessert, he extended an invitation to visit his grandchildren residing in a nearby condominium, which we happily accepted.

We reached his daughter’s condo at approximately 3.30pm, where we met his son-in-law, wife and two grandchildren engrossed in a Nintendo Switch game. The kids had a pet axolotl, a type of salamander called the Mexican Walking Fish. Curious, I approached the fish tank to examine the odd creature, which seemed to wear a constant smile. My curiosity was piqued, and I decided to look up axolotl on Google and learned that it could regenerate its body parts! I also found the Mexican Axolotl Optimisation-tuned (MAO) system, which utilises Internet of Things (IoT) sensors to precisely identify seismic activity. The system provides an early warning just seconds before an earthquake strikes, aimed at minimising potential damage. That’s cool, I thought to myself.

Immediately after learning about axolotls, I got an urgent message on my cellphone that said:

“EMERGENCY ALERT Earthquake Early Warning: Strong shaking is expected soon. Stay calm and seek shelter nearby (Japan Meteorological Agency).”

At that moment, I realised there wasn’t enough time to rush down to the ground from the seventh floor and find an open space. Roughly 20 seconds later, I felt the building tremble and noticed the water in the fish tank sloshing back and forth. My coffee cup mirrored the movement, leading me to imagine a swimming pool atop the condominium, creating a waterfall that I would see from our room’s window.

Unbothered

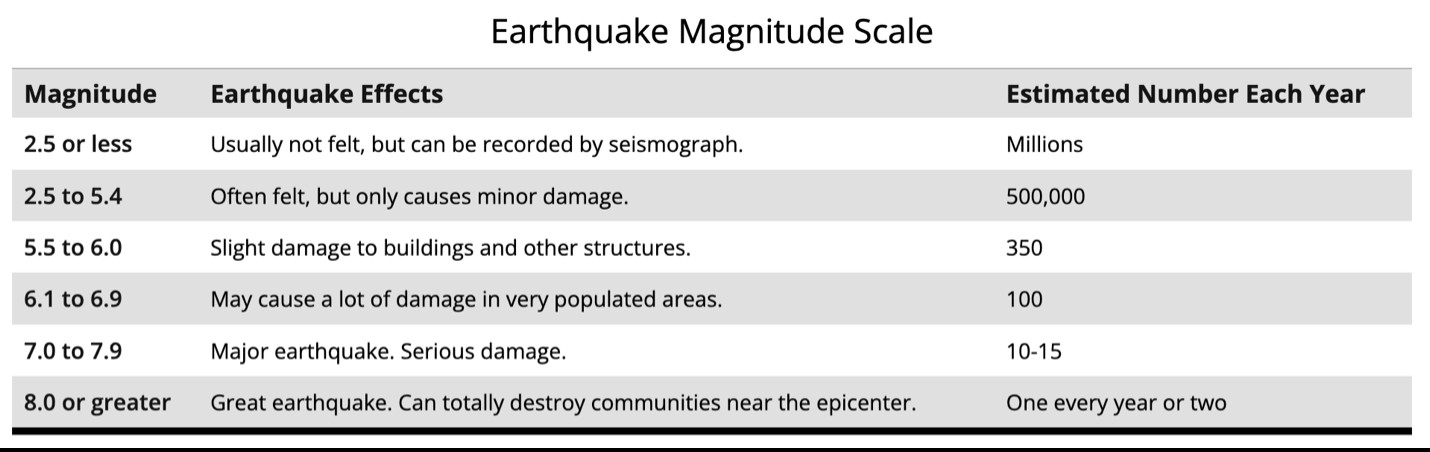

Frightened and anxious about the worst possible outcome, I attempted to remain composed. Uncertain of the earthquake’s magnitude and its point of origin, I could only guess that the shaking would last anywhere from 30 seconds to as long as two minutes. Earthquakes typically last that long, and during this time, individuals are advised to take shelter under a sturdy table to shield themselves from falling debris. We’ve also been told that once the shaking subsides, everyone must gather outside in an orderly manner until the building manager announces that it is safe to return.

Throughout the ordeal, I noticed that Eizo remained unbothered. He even crossed his legs while we discussed the ongoing earthquake. “Walang hiya, dumekwatro pa itong Hapon na ito [The nerve of this Japanese guy to even cross his legs],” I said to myself. His body language reassured everyone though, as if conveying that there was nothing to fear. He probably knew that the building, being newly constructed, adhered strictly to the Japanese Building Code, which required buildings to endure severe ground shaking. Perhaps he was confident that there were no shortcuts or under-the-table deals during the construction process. He might have even known that the building was equipped with seismic dampers designed to reduce vibrations and damage during earthquakes.